For decades, courts, state agencies, and state legislatures continue to ask the wrong questions in regards to state sales tax. This continuing practice has led to decades of inconsistent decisions in different states with similar laws. At the heart of the issue is the notion that the states have continually asked the wrong questions related to the policy and design of a sales tax regime. How could taxpayers expect correct results when the states continue to ask the wrong questions? However, it is this inconsistency that has allowed multi-state sales and use tax lawyers to continue to thrive in a marketplace growing with technology and complexity.

Without getting into a tedious history of a sales tax, the sales tax was essentially created during the Great Depression in the 1930’s. The first sales and use tax laws were hastily and poorly drafted and were copied from state to state to state. The sales tax regime was designed to tax individuals on the price of goods acquired for personal consumption. Conversely, the tax should not apply to the purchases made for business use, or what is known as “business inputs.”

In the early days, the easiest (not necessarily the correct) technique was to tax the retail sale of tangible personal property (“TPP”). It is this primitive ideal which is embedded in the original sales tax laws that have grown outdated and have created many of the issues in our much more complex economy of the 2000’s. Even with the changing of the times and the economy, our lawmakers and courts continue to ask the age old question that comes along with the foundation of the sales tax policy and design. Courts and lawmakers continue to struggle with what is “TPP” as opposed to real property. Why has no one stopped to think whether this should be the question at all? Shouldn’t the question be whether the goods are personally consumed as opposed to a business input? It is this fundamental problem and the states’ unwillingness to ask the correct question that has led to many of the inconsistent and puzzling rulings each year. This age old question has been and will continue to be problematic in effectively administering a state sales tax. However, the states’ stubbornness to ask the correct question will provide job security for multi-state sales tax attorneys for years to come.

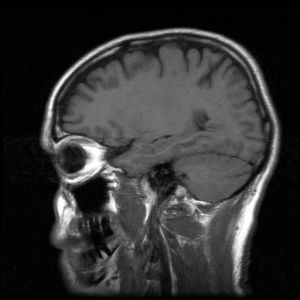

In a recurring classic example, Northeastern Pennsylvania Imaging Center v. Pennsylvania, 35 A. 3d 752 (Pa. 2011), the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania was faced with whether an MRI and PET Scan system purchased for over $2 million was subject to sales tax. The system weighed in excess of 15,000 pounds, took five days to install, could only be moved by crane, was anchored into the concrete beneath the floor, and could only be removed by removing the exterior wall.

The court opened its analysis by applying In re Appeal of Sheetz, 657 A. 2d 1011 (Pa. Cmwlth. 1995). In Sheetz, the court set forth a three part analysis to distinguish tangible from real property which looked to 1) the manner by which the property is affixed to land, 2) whether the property was essential to the property’s use, and 3) whether the affixed property was intended to be permanent. Applying this analysis, the court ruled in Sheetz that gas station canopies were real property, which is nontaxable from a sales tax perspective. Interestingly, the court used this analysis to uphold a property tax assessment in favor of the state.

Turning back to the MRI equipment, the court conveniently concluded the machines were merely movable cameras (taxable TPP) that “are removable and replaceable.” The court went on to use the crystal clear analogy by comparing the building’s use to house the MRI machines bolted into the underlying concrete to a garage built to house movable cars. The court went on to state the MRI machines were no different than the tangible washing machines in a laundromat or a pool table in a pool hall. Obviously in the three analogous situations, the construction was simply a means to house the equipment, “not a means of becoming one with it” because “[t]he real estate does not take the pictures.”

Perhaps by analogy one can infer that the court believes the canopies in Sheetz is real property because the canopy pumps the gasoline? It seems more likely that the court is doing the far too common practice seen by state and local tax lawyers in that it is first reaching a conclusion then justifying the result.

This case is just another example of the courts, under the legislature’s guidance, asking the wrong question. Rather than trying to cram a 15,000 pound “movable” camera into the taxable realm of TPP, the court should have been focusing on the fact that the property was a nontaxable business input. By applying the basic principles and goals of a sales tax, a grey decision instantly becomes more black and white. The recent Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision is one of dozens of examples each year that shows why states need to get back to the basics of the sales and use tax principles in order to generate revenue in a harsh economic environment.

About the author: Mr. Donnini is a multi-state sales and use tax attorney and an associate in the law firm Moffa, Gainor, & Sutton, PA, based in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Mr. Donnini’s primary practice is multi-state sales and use tax controversy. Mr. Donnini also practices in the areas of federal tax controversy, federal estate planning, and Florida probate. Mr. Donnini is currently pursuing his LL.M. in Taxation at NYU. If you have any questions please do not hesitate to contact him via email or phone listed on this page. For an in-depth look as to how Florida law applies to tangible versus real property please visit FloridaSalesTax.com

Multi-State Tax Law Blog

Multi-State Tax Law Blog